CAP Prize 2018 | Short List

CAP Prize 2018 | Short List

The following 25 artists – in alphabetical order – were selected by the CAP Prize panel of judges comprising 24 international curators, editors, publishers, and artists, from hundreds of applications for the CAP Prize 2018. Five of the shortlisted artists will be awarded the CAP Prize 2018 for Contemporary African Photography to be announced at photo basel in June 2018.

Jenevieve Aken

Born in 1989 in Ikom, Nigeria. Lives in Lagos, Nigeria

www.jenevieveaken.com | Instagram: @jenevieveaken

Monankim, 2017

Monankim is a word from the language of the Bakor people, a group of minority tribes from Cross River State, Nigeria. It refers to the process through which a girl is circumcised and celebrated as entering into womanhood. It is celebrated as a right of passage. A Monankim must be between the age of 14 and 18 and must be a virgin, after circumcision she is then held in a fattening room where she heals and recovers and is later presented to the community. She is idolised as a symbol of purity, a sexually mature woman who has remained a maiden, she is the pride of her family and a newly available and desirable wife. However, the rite of passage is not without its dangers. There are those who do not survive the circumcision, as the bleeding can be severe. For those who avoid that fate, the healing process takes place in the fattening room where the Monankim is accompanied, cared for and well fed by her female family members and friends. After two weeks she is presented to the community and the celebration takes place.

The project was realised after extensive interviews with young women, some of whom were frightened at the prospect, while others seemed excited and looked forward to their own time.

‘Monankim’ is a depiction of the artist’s contrasting traditional values, as she is herself from one of the minority tribes of the Bakor. The ritual is now highly controversial and stigmatised.

Yassine Alaoui Ismaili

Born in 1984 in Khouribga, Morocco. Lives in Casablanca, Morocco

www.yoriyas.com | Twitter: @yoriyas | Instagram: @yoriyas

Casablanca Not the Movie, 2014–2018

Casablanca Not the Movie is a long-term project that I started in 2014. It is both a love letter to the city I call home and an effort to nuance the visual record for those whose exposure to Morocco’s famous city is limited to guide book snapshots, film depictions or Orientalist fantasies. The title of the project references the classic 1942 movie Casablanca that was not filmed in the city, but rather in a Hollywood studio. Casablanca is a city of diverse cultures, shaped by numerous currents that may seem in opposition to one another. I want to convey the real street life and situations of Casablanca and highlights the moments where these cultures meet, which we wouldn’t notice if not in a photograph from the perspective of a Moroccan, who was born, grew up and still lives there.

Paul Botes

Born in 1972 in Johannesburg, South Africa. Lives in Johannesburg, South Africa

Twitter: @paulgbotes | Instagram: @paulbotes

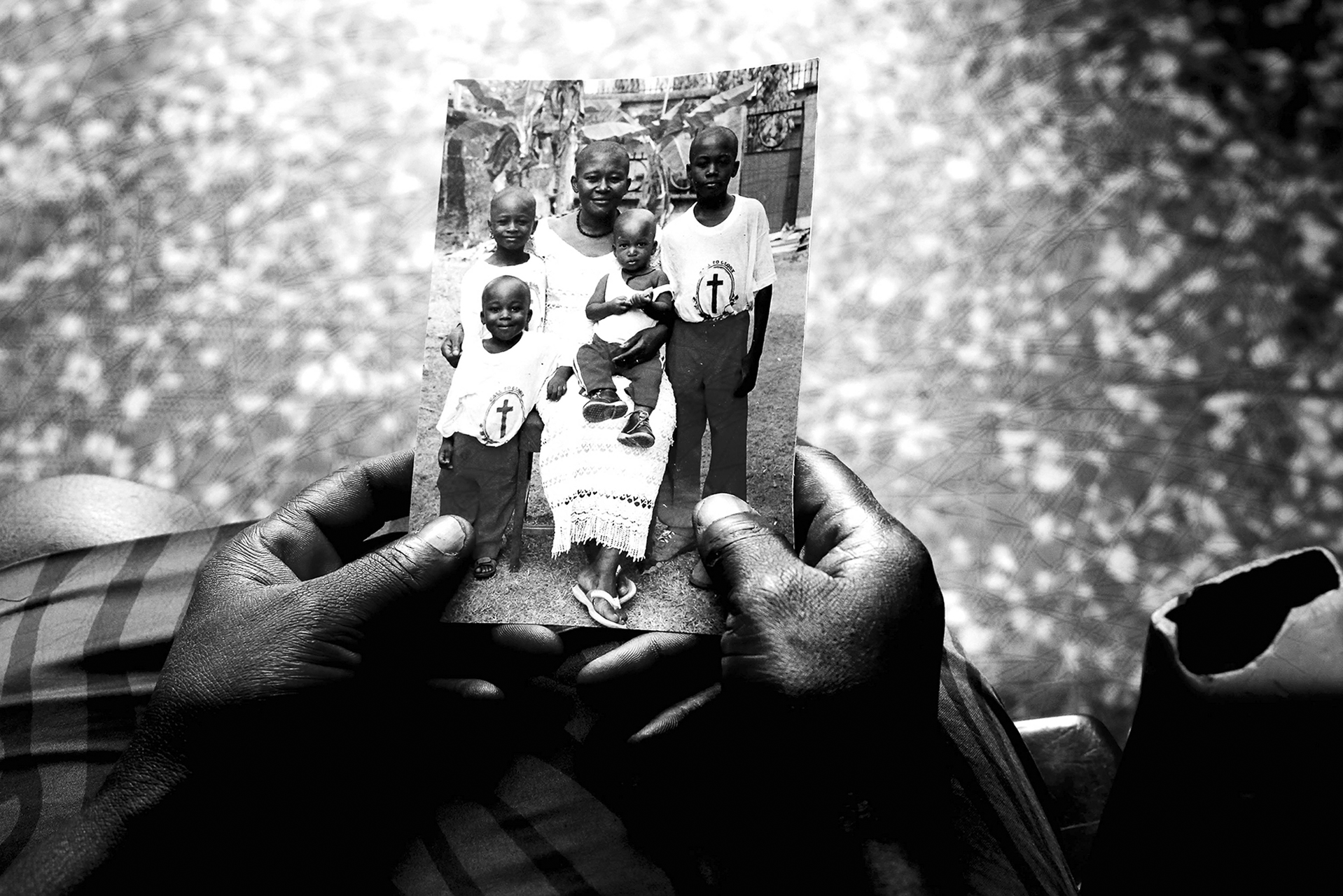

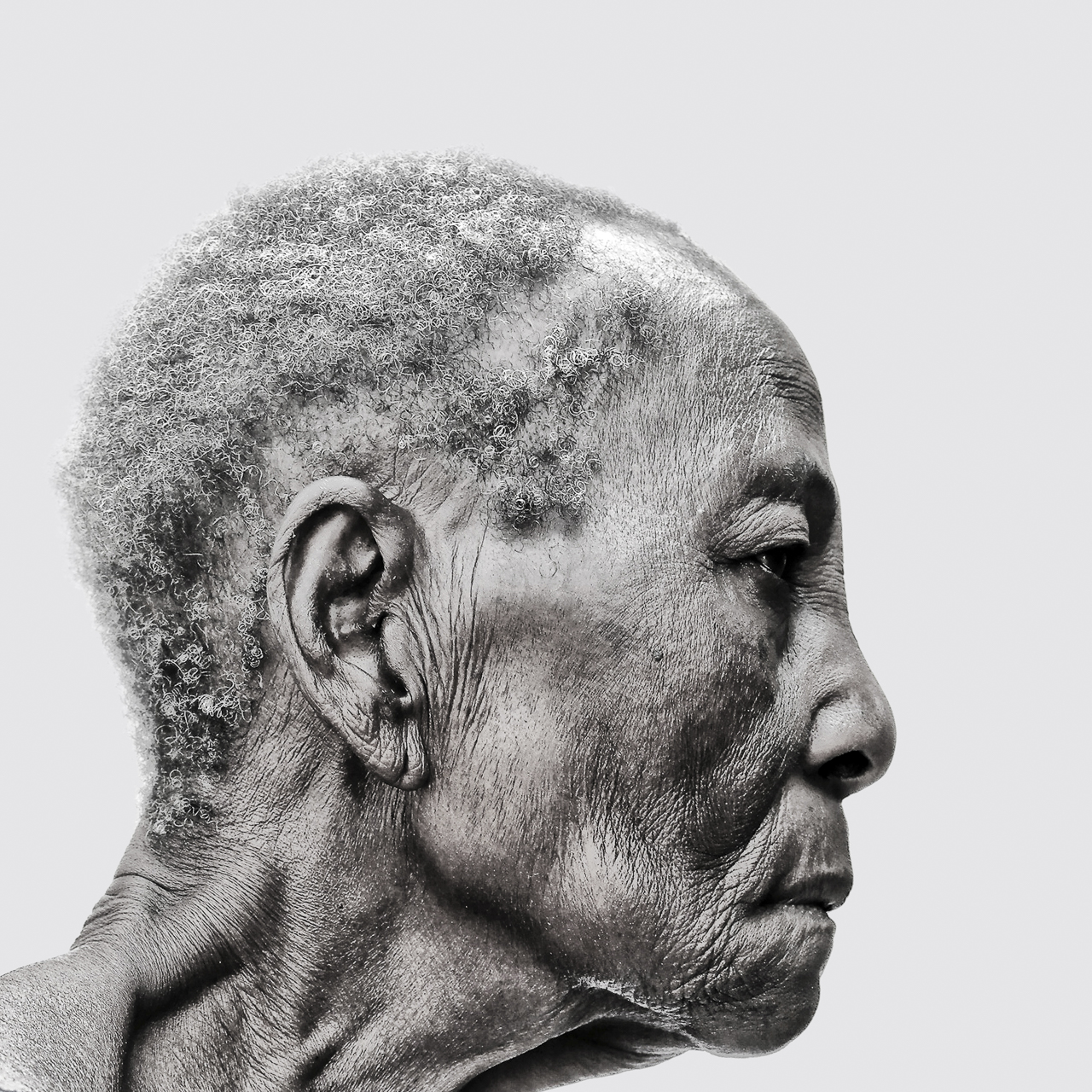

Marikana - The Aftermath, 2013 – on-going

The Marikana massacre on 16 August 2012 was the most lethal use of force by South African police since the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, and served as a brutal reawakening for post-apartheid SA. Thirty-four striking mine workers were killed; autopsies show many were shot in the back, the head, or at close range. This reconfigured the relationship between South Africans and an apparently progressive government.

This project was conceived after attending the funeral of Molefi Ntsoele, a mine worker killed in Marikana, in the remote village of Diputaneng in Lesotho. Understanding the massacre’s effects on the dead men’s families and communities became urgent because they were ignored in mainstream narratives.

The families come from marginalised and impoverished rural areas. They were criminalised by the state and denied counselling or financial support. Over the past five years I pursued my work through a process of “slow journalism” and “returning” to the families, with interviews sometimes doubling as therapy sessions.

The project reveals the financial and emotional vacuums created by the deaths and the effects on families and communities. As mineworkers’ children commit suicide and poverty deepens, the impact echoes for generations.

Mining’s migrant labour system requires barely educated men to build two lives: one, in the taverns, brothels and claustrophobic innards of SA; the other in the rural expanses to which they remit their salaries. This is where their ancestors’ spirits reside, informing an identity based upon culture, patriarchy and tradition.

The families are based mainly in the Eastern Cape and Lesotho, so these personal stories inevitably weave into an intricate quilt reflecting SA’s historical and contemporary relationship with the dehumanizing and emasculating migrant labour system.

It is critical that we remember the 44 dead and deepen our understanding of them, including the ten killed by police and striking mine workers in the week before the massacre, who are excluded from commemorations and ignored by mainstream narratives. Collecting family photographs and documents was essential in terms of 'humanising' the victims.

By exploring the massacre’s effects on families and communities with a history of mining migrancy, the project adds nuance and depth to understanding the socio-politics of contemporary SA.

Anna Boyiazis

Born in 1967 in Los Angeles, USA. Lives in Los Angeles, USA.

www.annaboyiazis.com | Instagram: @annaboyiazis

Finding Freedom in the Water, 2016

Daily life in the Zanzibar Archipelago centers around the sea, yet the majority of girls who inhabit the islands never acquire even the most fundamental swimming skills. Conservative Islamic culture and the absence of modest swimwear have compelled community leaders to discourage girls from swimming. Until now.

For the past few years, the Panje Project has made it possible for local women and girls to get into the water, not only teaching them swimming skills but also aquatic safety and drowning prevention techniques. The group has empowered its students to teach others, creating a sustainable cycle. Students are also provided full-length swimsuits, so that they can enter the water without compromising their cultural and religious beliefs.

While the wearing of full-length swimsuits may be seen as subjugation, donning one in order to learn a vital life skill, which has long been and would otherwise be forbidden, is an important first step towards emancipation. Education — whether in or out of the water — serves as a springboard that provides women and girls with the empowerment and tools with which to claim their rights and challenge existing barriers.

The rate of drowning on the African continent is the highest in the world. Still, many community leaders have yet to warm up to the idea of women and girls learning to swim. The lessons challenge a patriarchal system that discourages women from pursuing activities other than domestic tasks. It is this tension between the freedom one feels in and under water and the limitations imposed upon Zanzibari women that is at the heart of this series.

David Chancellor

Born in 1961 in London, United Kingdom. Lives in Cape Town, South Africa

www.davidchancellor.com | Twitter: @chancellordavid | Instagram: @chancellordavid

With Butterflies, and Warriors – the story of community-based conservation in the northern rangelands of Kenya, 2014–ongoing

The poaching of wildlife is well documented and should not be underplayed. However, what remains largely unseen is the important part that local communities play in conserving and protecting the wildlife that they live alongside.

This is the story of those communities in northern Kenya who have come together as a collective of community conservancies in order that they may safeguard the future of a wide range of species.

The future of wildlife in northern Kenya will require support and engagement from local communities, thus allowing the safe migration of wildlife along centuries-old routes across tribal lands. This is particularly important for species such as Grevy's zebra, and elephant, who have large home ranges and require access to large tracts of land.

The majority of Kenya's wildlife exists outside the network of national parks and reserves, predominantly in private and community conservancies, and on community land. Most of the northern rangelands are community-owned and still host abundant wildlife, although most local people accrue no benefit from the wildlife with which they share their land, and until now have seen no value in protecting it. Indeed those communities with land suitable for conservation have until recently had no access to the expertise, resources, or the donor agencies that are required to develop community-based conservation.

However, all this is beginning to change and communities are starting to see the benefits from the dual use of wildlife and livestock. There is a realisation that wildlife can be used alongside livestock to generate the capital needed to help communities improve their welfare and bring peace, thus giving them a clear financial stake in preserving wildlife, rather than killing it. The incentive is now to protect wildlife and as a result 'an enemy of wildlife is now also an enemy of the people'.

In addition, as a result of the increased security for both people and wildlife, the safari industry, a pillar of the Kenyan economy, generating more than a billion dollars a year, is also beginning to return tourists to an area where most would have previously feared to tread. However, with the incredible amount of money being offered to those who do poach, this fragile peace and security hangs in the balance as these communities are also on the front line of the current poaching war which threatens to undermine all their recent successes.

The northern rangelands is also an area vulnerable to the vagaries of climate change; drought and flood can have devastating effects on both people and wildlife, thus exacerbating the possibility of human wildlife conflicts as pastoralists compete with wildlife for diminishing resources..

Baptiste de Ville d'Avray

Born in 1982 in Paris France. Lives in Lisbon, Portugal

www.baptiste-dva.fr | Instagram: @ayonimorocco

So far away yet so close, 2009–2017

The project “So far away, yet so close” brings together seven years of exploration on a real territory, during a boom in urban development – a place that is resolutely contemporary and yet photographed in a timeless manner.

I originally approached Morocco during regular short visits. What attracted me was the unique Atlantic atmosphere and the coastline spanning thousands of kilometres between the Algerian and Mauritanian borders. This country became a character in its own right. I constantly revisit and chisel away at this material, honing a landscape that springs from my mind. I tried use my camera to transform atmospheres and slices of life into stories. The characters are like silent actors who appear to perform in a set I invented that is always softly lit.

I began the series Mediterrannea Saidia in 2009, focusing on the “Plan Azur” project, with the scheduled creation of six seaside resorts. This series features the concrete sprawl over the coastline, through architecture and landscapes whose residents appear lost.

Shortly after the events that shook the Arab countries, I continued my work on the coast with the series Witnesses on the horizon [A l’horizon les témoins]. These photographs capture a latent expectation in the air, at once calm yet full of tension, which can be found in many Mediterranean countries. Facing the sea, the witnesses wander. They pause, impassive. With their eyes turned to the future, they seem to deny themselves the right to dream.

In 2012, I moved to Morocco and began a contemplative photographic fiction compiled over the course of my travels and encounters, with So far away, yet so close [L’apparition d’un lointain si proche]. This was the starting point for playing on the fringes of my practice, by moving away from a more documentary and serial approach. In each photo time appears to slow down, with each of the titles reconstituting the pieces of a puzzle to form a fable.

I later embarked upon a nomadic photography project The Coast : another border [Le littoral, une autre frontière], which follows the Moroccan side of the Mediterranean bypass that was never completed, originally intended to link up two countries, Algeria and Morocco. In this series I tried to reveal the radical transformations of the landscape with a cinematographic style.

In 2016, while living between two continents, I began Postcard from Morocco: a kind of visual and imaginary correspondence. In this series, i present suspended moments devoid of exoticism.

Ulla Deventer

Born i 1984 in Henstedt-Ulzburg, Germany. Lives in Hamburg, Germany.

www.ulladeventer.com | Instagram: @ulladeventer

Butterflies are a Sign of a Good Thing, 2017

Since 2013 I have been working on a long-term art project concerning women working as prostitutes. My main motivation for engaging with this subject has been to reveal unexpected views on this topic, thereby tackling the stigma that is attached to it.

“Butterflies Are a Sign of a Good Thing” is an observational research project about women living in Accra, the capital of Ghana, and its surrounding neighborhoods. The series focuses on their survival methods within a place that offers few economic opportunities. This project is the continuation of my long-term project, “I’ve Never Been Big Sick,” which addresses women working as prostitutes in Western Europe. I have met several African women from places like Nigeria and Ghana through my experiences exploring prostitution in Western Europe. I became familiar with their attitudes and culture, which they try to preserve in their new cultural environment. My relationships with the protagonists in my images are very important to me. These women are incredibly inspiring and I am close friends with a number of them. I have always hoped to visit their home countries to learn more about them and their experiences.

In May 2017, I went to Accra for six weeks thanks to a generous grant from the VG Bildkunst and in collaboration with the US video artist P Sam Kessie. Exploring Accra and the surrounding neighborhoods was the starting point for a multifaceted research project on the living conditions and experiences of young people in Accra, particularly sex workers, who dream of leaving their country. Old tragedies and nightmares fuel an inner strength to survive in a society plagued by economic hardships, religious restrictions, and strong misogynistic views.

This series can be extended with interviews, videos and drawings made by the protagonists into a poetic multimedia piece that shows a female outsider’s perspective on the present-day lives of young women in Accra. The project addresses this while staying open to an imaginative perspective; it creates imagery rich in atmosphere and emotions based on real-life clues, rather than straightforwardly documenting reality.

Adji Dieye

Born in 1991 in Milano, Italy. Lives in Bern, Switzerland

www.adjidieye.com | Instagram: @adjigiagi

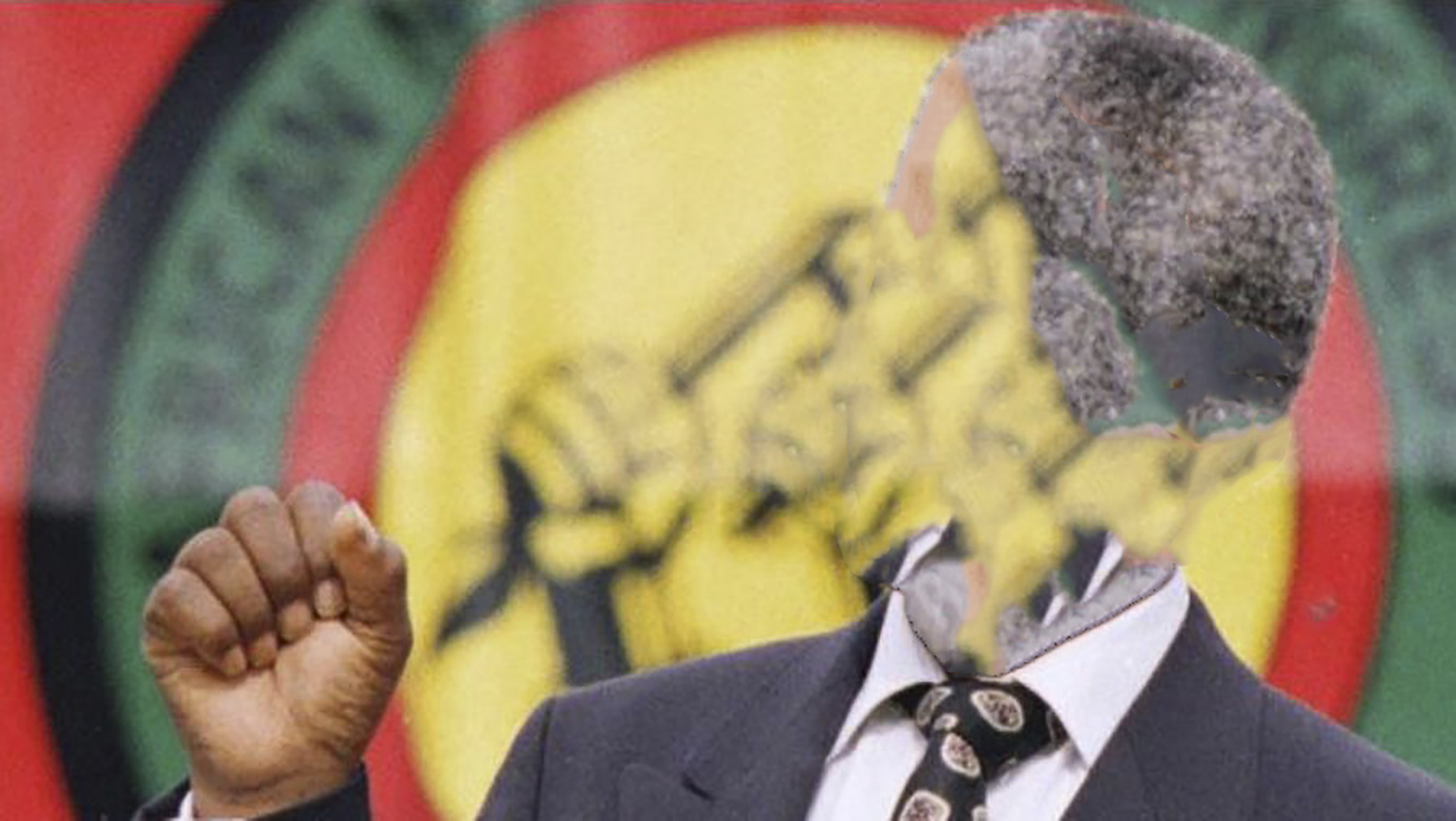

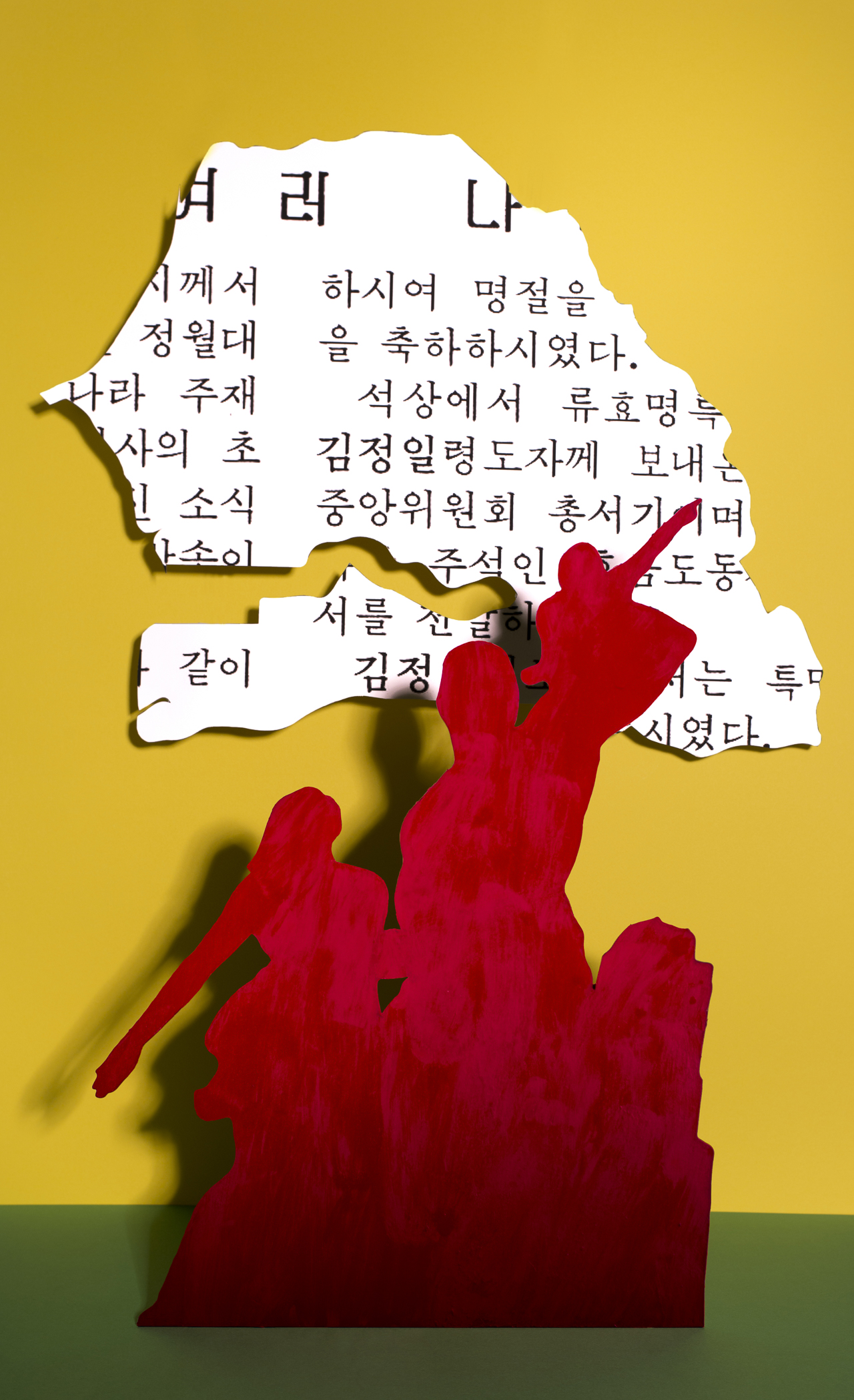

Red Fever, 2017

Red Fever is a photographic project that aims to explore the spread of socialism throughout Africa and the traces it left on the continent through images, photos and photomontages.

Juxtaposing the real and the false, tampering with history itself, artist Adji Dieye looks at this period - until now largely unexplored - with fresh eyes, as if it were something coming from a parallel reality. The leaders and dictators become phantoms of themselves; not forgiven, but often forgotten by the West, they leave space to an orthodox ideology from which they usually distanced themselves. Soviet blocs in the jungle, constructivist towers, and monuments in the middle of the Savanna seem to describe a peculiar retro afro-future imagined 50 years ago. A possibility that never came to be realized but that continues to fascinate us.

With her images of the past and an imagined communism in Africa, Dieye presents and preserves the last dream of a polycentric world where everything doesn’t have to pass under the surveillance of the neo-liberal West. While not idealizing or cleansing in any way the history that comes with the red fever, the idea of choice of political system is today becoming more and more difficult to imagine, making this project even more relevant.

At the same time, Dieye enquires into the possibility of a system-world without a monolithic structure through images of monuments and statues produced by North Korean firm Mansudae Art Studio all over the African continent. In this silenced and surreal relationship between the Hermit Kingdom and 16 different African countries, we find the embodiment of our post-Westphalian world condition. Defying all agreements with the United Nations, states like Namibia or Mozambique kept profitable accords with North Korea, becoming de facto a ring in a chain that moved money from the UN to the Pyongyang regime, one of their most feared enemies. An air of cold war rises while the nuclear threat from both sides of the Pacific increases.

Only traces of this socialist genealogy of Africa, these monuments, red and flattened, open a discussion about the political power of representation and its impact on the construction of the identity of a people. Not one to shy away from a critique, Dieye points out the absurdity of the propaganda these monuments spread through their statements, putting them side by side with an almost playful and paper-like version of themselves.

Ralph Eluehike

Born in 1978 in Ndemili, Nigeria. Lives in Lagos, Nigeria

Instagram: @ralph.eluehike

Shadows of Domestic Work, 2016–2018

Shadows of Domestic Work as an ongoing series is a voyage that uses a performance concept in the medium of photography to highlight the various ways in which domestic workers are ill-treated by various individuals or homes. As the name implies, Shadows depicts the negative side of domestic work. It is fast becoming a contemporary issue when it comes to the degree of ill-treatment of these workers by individuals who are supposed to be a guide or a brace to some of these workers who are either economically or naturally deprived of some of the basic life necessities. Estimates suggests that there are at least 64.5 million domestic workers worldwide. Most of these domestic workers live in abject poverty and lead a life of reckless abandonment.

On a direct intersection coupled with adequate interaction with these individuals, I realized that they are living a life of torture, hopelessness, no formal education and virtual imprisonment. They are sometimes used to entertain the elites. They see the world from a distance; there is a virtual barricade between them and the outside world. Like each one of us they have dreams and aspirations, but their dreams are encapsulated.

I am working on this project in order to be a voice to the voiceless by bringing to the attention of all concerned individuals and institutions the rate at which this ugly phenomenon is eating into the bedrock of our societies.

Makeup/Costumier: Blessing Emorike

Patricia Esteve

Born in 1972 in Barcelona, Spain. Lives in Nairobi, Kenya

www.patriciaesteve.com

Out of this Life, 2015–2017

When Anita’s father died by suicide she felt guilty and sad because she hadn’t helped him. Apart from grappling with the sorrow of their loss, her family was also faced with the stigma of the suicide. As a condition for burying her father’s body, the community of her village in West Kenya forced all her family to drink a herbal infusion to purge the “evil spirit” from her father’s body and prevent the village from being plagued by any further suicides. Later that night they buried the body and didn’t allow the family to attend the funeral. The family was locked inside their house and they couldn’t mourn him. For the next year they were isolated from all social events; wherever they went people avoided them.

Out of this life uses images based on true stories such as that of Anita and her family in order to explore the approach to suicide in Kenya. The project comprises a collection of testimonies from people who have tried to commit suicide or have lost a loved one to suicide and have faced the ensuing stigma as well as social and legal injustice. According to the Kenyan Law Nº226 of the penal code, anyone who attempts to commit suicide is guilty of a crime.

The project was created by compiling the stories of people who have suffered through the experience of suicide and its consequences. The interviewees were asked to write texts about their experiences, which were later illustrated using the information gathered both in the interviews and from the texts. This combination of images and words creates a visual narrative that supports the visualisation of suicide from an intimate and poetic perspective. This in turn leads us to an emotional level of understanding and help us to put ourselves in the place of the other, leaving any possible prejudice behind us.

This project is an invitation to partake in a crucial dialogue in any society that condemns suicide on cultural, religious, or social grounds.

Nneka Iwunna Ezemezue

Born in 1985 in Lagos, Nigeria. Lives in Lagos, Nigeria

www.nnekaiwunna.com | Instagram: @nnekaezemezue

Left Behind, 2017

For many women, becoming a widow does not just mean losing one’s husband; often it means losing everything else as well. In many developing countries, a woman who is widowed becomes a non-person. This project is a reminder of the women who are Left Behind in their widowhood.

Left Behind is a project that examines the plight of widows in Nigeria. They are compelled to go through the mandatory observance of prescribed burial rituals, which vary across cultures. Widowhood robs them of their status and consigns them to suffer social discrimination, stigma and even violence. In some communities, a widow is forced to perform inhuman burial rituals such as sitting unclad on a floor for a period of time without a bath, drinking the bathwater of the corpse, shaving her hair completely, crying or screaming aloud, or being prevented from seeing the corpse of her husband. The reasons given for this inhuman treatment are that it is necessary for proving the widow’s innocence, that it shows respect the dead, facilitates the movement of the husband’s spirit to the spirit world and thereby protects the living from the dead.

Most of the women I photographed are Igbos, from the South Eastern part of Nigeria where the practice of extreme forms of inhuman burial rituals is commonplace. For them, mourning rituals are an ancient practice enforced by the men and implemented by the ‘Umuada’ (first daughters of the town). Many communities have abolished the barbaric practices, but others are obstinate because they claim it is tradition.

The project comprises a series of portraits of the widows, as well as images of objects relating to their stories. Gaining access to the widows was a big challenge.

This project was supported by Magnum Foundation

Jonas Feige & Yana Wernicke

Born in 1988 in Frankfurt, Germany. Lives in Berlin, Germany

Born in in 1990 in Hochheim, Germany. Lives in Berlin, Germany

www.jonasfeige.com | www.yanawernicke.com

Zenkeri, 2013–2017

Zenkeri is a collaborative project about the repercussions of the life of German colonialist Georg August Zenker.

In 1889 the German botanist and gardener Georg August Zenker settled in Bipindi, a small patch of land in the then German colony of "Kamerun". Here Zenker – who was raising a family with a woman from Togo – built a colonial style villa, established a plantation and worked as a botanist, collector and zoologist for museums in Berlin. His villa is still home to his descendants, who today struggle to reconcile their German and Cameroonian identities.

Our project consists of many different parts: our own photographs from Bipindi, a photographic exploration of the property as well as portraits of the family members; found photographs and texts from the family archives and other historical sources; photographs of the countless plant and animal specimen as well as ethnological objects that Zenker sent to Germany and that can still be seen in museums today.

Through our project we have come to see the villa in Bipindi as somewhat of a spaceship from a different planet; one that Zenker landed in an exotic place to make his home, unaware of how it might affect his descendants, both in their own search for identity and in terms of how they might be looked upon by the native inhabitants of the land. Being German ourselves, we were fascinated to find a piece of our own country’s history in the middle of the Cameroonian jungle. We were moved by a family’s struggle with their own identity that stems from a shared past which has for the most part been forgotten in Germany.

Through interviews that we conducted with family members in Cameroon, France, Belgium and Germany, we came to understand that there are many questions that are still far from resolved. There seems to be a strong disconnect between the family’s personal historical narrative and the historians’ quasi official version. With our portrait of the family Zenker we hope to raise broader questions surrounding the still palpable repercussions of German colonialism in Africa and specifically Cameroon.

Tommaso Fiscaletti & Nic Grobler

Born in 1981 in Cattolica, Italy. Lives in Cape Town, South Africa

Born in 1979 in Pretoria, South Africa. Lives in Cape Town, South Africa

www.hemelliggaam.com | Instagram: @tofisca | @nicgrobler

Hemelliggaam or The Attempt to be Here Now, 2016–2018

Hemelliggaam (Afrikaans: Heavenly Body) or The Attempt To Be Here Now, is a visual exploration of the existential aspects of the human-environment-astronomy relationship. Inspired by South African Science Fiction writings, the project explores the interplay between scientific astronomical activity and everyday awareness of space through a contemporary lens. The project makes particular reference to Jan Rabie, one of the most existential and emblematic writers, who wrote the books 'Swart Ster oor die Karoo' (Black Star over the Karoo, 1957), Die Groen Planeet (The Green Planet, 1961) and 'Die Hemelblom' (Heaven Flower), 1971. The focus of the project is on communities, landscapes and objects located in the Western and Northern Cape, South Africa, where the sky is particularly impressive.

Something archaic radiates from the local community in connection with their science and technology needs, this project is exploring this concept through looking at forms of awareness that are already active and cultivating more awareness through conversations, participation and reflection.

“Hemelliggaam or The Attempt To Be Here Now” follows a deeply existential line, where the human beings (both the old and contemporary) through their own perception of the Universe is strongly connected with nature and the way it reveals itself.

The project has been shot on 120 Film Kodak

Jason Florio

Born in 1965 in Kingston, United Kingdom. Lives in St Julians, Malta

www.floriophoto.com | Instagram: @jasonflorio

Destination Europe, 2015–2016

During 2015 and 2016 I was assigned to document the work of MOAS, an NGO rescue ship specifically set up to save the lives of migrants attempting to cross the Mediterranean from Libya to Europe.

Since 1998 I have lived on and off in The Gambia, West Africa. During my stays in The Gambia I regularly met the friends and relatives of young men and women who had left for or drowned in the Mediterranean while trying to take 'the back way' - as the illegal route to Europe through Libya is colloquially called - in search of work, greener pastures, and sometimes just out of youthful curiosity.

Initially, my embed with MOAS was ‘just another assignment', but soon we were rescuing not only Somalis, Sudanese and Nigerians fleeing conflicts, but many Gambians escaping a dictatorship and poverty, which I was all too familiar with from my time there. My work quickly began to take on an added personal role, when among the first group of rescued Gambians I met 18-year-old Sana Colley, who was the son of a friend of mine back in The Gambia.

Encounters with rescued Gambians with whom I had close personal ties continued to occur. Wherever possible I would call their relatives back in The Gambia, from onboard the ship, to inform them their loved ones were safe. My initial embed was for three weeks, but I was soon so emotionally invested in the story that I stayed on for multiple sea missions spanning two years.

Having left my own country nearly thirty years prior in search of a ‘new life’, I did not see the Africans and especially the Gambians I met at sea as ‘other’ or defined by their temporary status as ‘migrants’, but as fellow travellers on paths that were intersecting mine. I see the work not just as a document of Europe’s ‘migration crisis’, as the photographs have also taken on the added significance of souvenirs: Many of the ‘travellers’ contact me for pictures of their rescues to send to family and friends, and as a visual reminder of their journey to a ‘new life’.

Akpo Ishola

Born in 1983 in Yopougon, Ivory Coast. Lives in Cotonou, Benin

Instagram: @isholaakpo_artistevisuel

L'essentiel est invisible pour les yeux, 2014

This photographic series is part of an approach to conceptual art and documentary. In this work the photographer explores the story of her grandmother through the remaining objects from the dowry of her marriage: wooden canteen produced by her future husband, cloths, beads, gin bottles, bowls, mirrors etc. These are goods that the groom's family brings as a symbol to seal the alliance between two families, two clans, two ethnic groups, materializing their mutual consent. Thus in an extended family of vision, it is estimated a couple is not built by the man alone, but with the help of relatives, and first by the respective families. This system helps to register couples in the period in community logic. By photographing the remains of this dot, Ishola Akpo attempts to show that the object never revealed is the silent witness. Each frame carries a set of memories experienced by the couple, but also imagined and fantasized by the viewer who projects his own stories about the objects.

These images also have a meaningful potential to grandmother became the photographer of both object and subject of the report. These objects revive his memories and his memory and also reveal the anguish of those who feel old and want to leave a trace of their passage in the family memory. These rusted and worn objects have aged with the woman, they bear the imprint of time as she carries on her beautiful weathered face, her wrinkles and gray hair. But they also celebrate the lives of Dossi.

By speaking of this personal and intimate story and by using his own grandmother as a subject, Ishola Akpo highlights the importance of the dowry he received 80 years ago and reflects on a strong African tradition in the first anchoring in its own history and its subjectivity. This step is for the artist the first of a global reflection on the issue of dowry he wishes to continue imagining what could be the dots in the future. plastic project as much as societal, this series talks about the traditions that underpin our cultures and how they are perceived today through the eyes of a little son on his grandmother, looking both confused, loving, critical but aware that he cannot see all the essential is invisible to the eyes.

Delio Jasse

Born in 1980 in Luanda, Angola. Lives in Milano, Italy

www.deliojasse.com | Instagram: @deliojasse

Cidade em movimento, 2016

The city of Luanda is haunted by its history. The architecture, the infrastructure and the inhabitants are an embodiment of the city’s social make-up and its continual change throughout time. It is an awareness of Luanda that drives Delio Jasse’s practice, and his assertion that “Luanda is an exercise in memory” is vividly portrayed in the series Cidade em Movimento. Cidade em Movimento was produced in 2016 and comprises 24 cyanotypes that depict the materiality of the street and reflects upon the rapid social and economic changes that have underpinned recent shifts in the urban landscape of Luanda.

A few years ago, Luanda was on every ambitious investor’s lips. Angola is the second largest producer of oil in Africa, and when the international price of crude oil reached a peak in 2008, the oil boom transformed the nation into one of the world’s fastest-growing economies. With large infrastructure and housing projects rapidly changing its appearance, Luanda seemed to be leaving behind the country’s 27-year civil war. But since oil prices crashed in 2014, the impact on one of Africa’s richest and most unequal countries has been devastating. The same officials who boasted of Luanda’s sparkling ascent are asking for billions of dollars in loans.

The works in Cidade em Movimento (2016) were shot after oil prices fell in 2014 and convey a sense of stillness and disillusion: International property development projects that had encompassed the economic identity of Luanda prior to the crisis have been placed on hold and Luanda is mostly standing still. Jasse reflects on the ambiguity of movement and stillness. The architecture of Luanda, simultaneously the background and foreground of the works, invite feelings of a city in waiting. Within the picture frame, however, we witness the city’s inhabitants in transit, from one location to another. A paradox ensues as the camera freezes their movements in time and space. This static state is a contemplation not only on the economic crisis that resulted in Angola, but also of the political uncertainty and suspense of the presidential elections that would occur a year later. Jasse effectively portrays the quotidian manifestations of Luanda’s people who are seemingly wedged in their present lives as they meditate on the ambiguity of their futures.

With this series, Jasse pursues his interest in printing techniques. The cyanotype is a fitting printing method for a series concerned with architecture (the architectural blueprint is a variation of this printing process), but the rich blue-green hue of the photographs contrasts sharply with the dusty, sandy atmosphere of the sprawling metropolis, creating a manifest distance with reality. Working exclusively with analogue techniques, including liquid emulsions and manual filters, the artist often disrupts his own imagery, showing tape marks, cutter lines and other signs of manual handling and editing. As Jasse writes: “The manipulation [...] enables me to create a new image, one that didn’t exist before. The image thus occupies a space that is neither completely real nor completely fictitious, neither reality nor memory”.

Phumzile Khanyile

Born 1991 in Soweto, South Africa. Lives in Midrand, South Africa

Twitter: @TheeDelaRoss | Instagram: @phum_zile

Plastic Crowns, 2016

Plastic Crowns stems from the idea of taking a perceived “prestigious” ornament such as a royal or beauty pageant crown and turning it into an object that anyone can purchase and thus enthrone themselves. It is the constant reconception and reinvention of the self.

I explore beyond the tragic boundaries of what my grandmother would consider a “good woman”, probing stereotypical ideas of gender, sexual preference and related stigmas and their relevance in contemporary society. I am interested in how having multiple partners (balloons) can be an expression of choice as opposed to it being an indicator of low morality, based on societal conventions.

This body of work is a journey of self-discovery. Being raised by my grandmother who had stereotypical ideas of what it means to be a woman often left me feeling suffocated. I find it ironic that such ideas never worked out for her; I took photographs inside the house she received as a divorce settlement while she preached to me that time was running out for me to get married. My grandmother never understood photography so I would photograph in secret whenever she was at church or asleep.

Going through my family album and seeing how curated it was, I wanted to unveil the dysfunction and speak about what really happens behind closed doors.

I keep a journal regarding what I am going through internally, which is influenced by both memory and the present; how I remember the women in my family from my childhood and teenage years, and the realisation that what I took for strength at the time was actually survival.

Looking back it is ridiculous that women in my grandmother’s day would sneak off to the bathroom to hide the fact that they were smoking, but it’s also funny how the smell would escape through the doors and windows. I remember that smell.

Placing headscarves and a chiffon dress over my camera mimicked the feeling of film, but also allowed me to view the space differently, disrupted, which echoed what I already felt.

This work is me wrestling.

What if we allowed girls to sit with their legs open too..

Bas Losekoot

Born in 1979 in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Lives in Amsterdam, The Netherlands

www.theurbanmillenniumproject.com

Familiar Strangers, 2016

Wandering the city can feel like dreaming sometimes. There is something simultaneously foreign and intimate about that: The space of a dream is strange and alien, yet at the same time as close to us as possible. The phantasmagorias of our dreams still operative in our daily lives. They create worlds that are both strange and familiar. In this photographic series I am trying to evoke this uncanny feeling and activate collective memory of places and people seen in media. Working with cinematic apparatuses, I like to challenge the understanding of reality in everyday city life as well as the limited narrative potential of representations of truth in documentary photography. I hope to leave the viewer in uncertainty about what he is really looking at; is it fact or fiction, a documentary or a staged photograph?

We are now facing the biggest wave of urbanisation in human history since the beginning of the Urban Millennium. How is this fast-growing population density influencing the behavior of everyday commuters in the streets of the world’s most crowded megacities?

At the moment Lagos is expanding rapidly; more than 58 people enter the city every hour, in search of a better future. By 2050 the predicted population of Lagos State will be 36 million people. It might become the third biggest city in the world, and yet there is still so much we don’t know about the city. In terms of size it truly is a megacity, although at micro level the social structure on the street is akin to that of a tribe or small village; it seems as though most people are familiar with one another. In Lagos the concept of the 'stranger' - a member of the group that remains distant - is reinvented. I like to consider these people 'familiar strangers’; citizens who recognize each other yet do not interact when in close proximity. The familiar stranger is the one we know but do not know anything about. Lagos street life is a continuous stream of split-second meetings where urban encounters can become brief sublime experiences.

I always considered the street a stage where we, the actors, are performing in the decor of the city. In daily life we perform social roles and we wear the mask appropriate to this performance. While commuting the city we drop this mask and replace it with another; the mask of ‘self-protection’. I am interested in this mask because I believe it provides us with a lot of information about the self and the construction of identity. In order to decode the city we have to understand its 'soft' side. Cities are not only constructed by our memories, but also how we perceive them through our imagination, myths and dreams.

“To understand the city as a psychological and cinematic place helps to bring people together in the future in a way that makes a difference to what goes on between them” - Steve Pile (2005) Real Cities

In 2011, I started a visual exploration of the consequences of growing population density. I selected nine fast-growing megacities around the world that either house 20 million inhabitants or will reach this number in the next couple of years. How do people react to each other in areas of overpopulation? What impact does this excessive growth have on our sense of personal space in the public domain?

The cities I photograph are ‘on the move’ and its inhabitants are in transit. This in-between-ness represents the present urban state of mind and unfocused attention of the city dwellers. Metropolitan life over-stimulates our senses and we react with indifference and a blasé attitude. With the help of telephones, headphones and sunglasses, we detach from space and reality. I am drawn to the working of the arresting shutter: the unique quality of photography to arrest movement. I try to capture offbeat moments that remain unseen at the everyday speed of life.

The photographs of Lagos are part of the long-term project "In Company of Strangers" that explores the cities of New York, Sao Paulo, Seoul, Mumbai, Hong Kong, London, Istanbul and Mexico City. This project will be presented as a book that provides a sociological insight into the human condition in contemporary megacities around the world.

Esther Mbabazi

Born in 1995 in Mengo, Uganda. Lives in Kampala, Uganda

www.esthermbabazi.com | Instagram: @esther_mbabazi

The Things We Carry, 2017

This project documents the most important things that people carry with them when fleeing conflict and war. In times of trouble, when one leaves their home behind and walks long distances lasting days, weeks or months - what is the one item they carry with them that means a lot in their lives?

I documented South Sudanese refugees living in a Bidi Bidi refugee camp in the Yumbe district in northern Uganda. Uganda is the third country hosting the largest number of refugees in the world, but the way refugees are documented is in many cases less dignifying and this is leading to many people not welcoming refugees and some people treating refugees as lesser people in the host countries.

Through these portraits and objects, we can see people for who they are without branding them. The items they carried could be anywhere or anyone's - this series is meant to ask the audience to look and view the people photographed for who they are. I use quotes taken from the interviews to stress how important these items are to the people carrying them. The simplicity in the objects draws a big understanding about who the people photographed are, what matters in their lives, and a part of their life story is shared with the audience. I photographed the items on a uniform background of the UNHCR mats that every household in the camp is given in order to give a visual sense of belonging amongst the people photographed.

Venetia Menzies

Born in 1992 in Edinburgh, Scotland. Lives in Edinburgh, Scotland

www.venetiamenzies.com | Instagram: @venetiamenzies

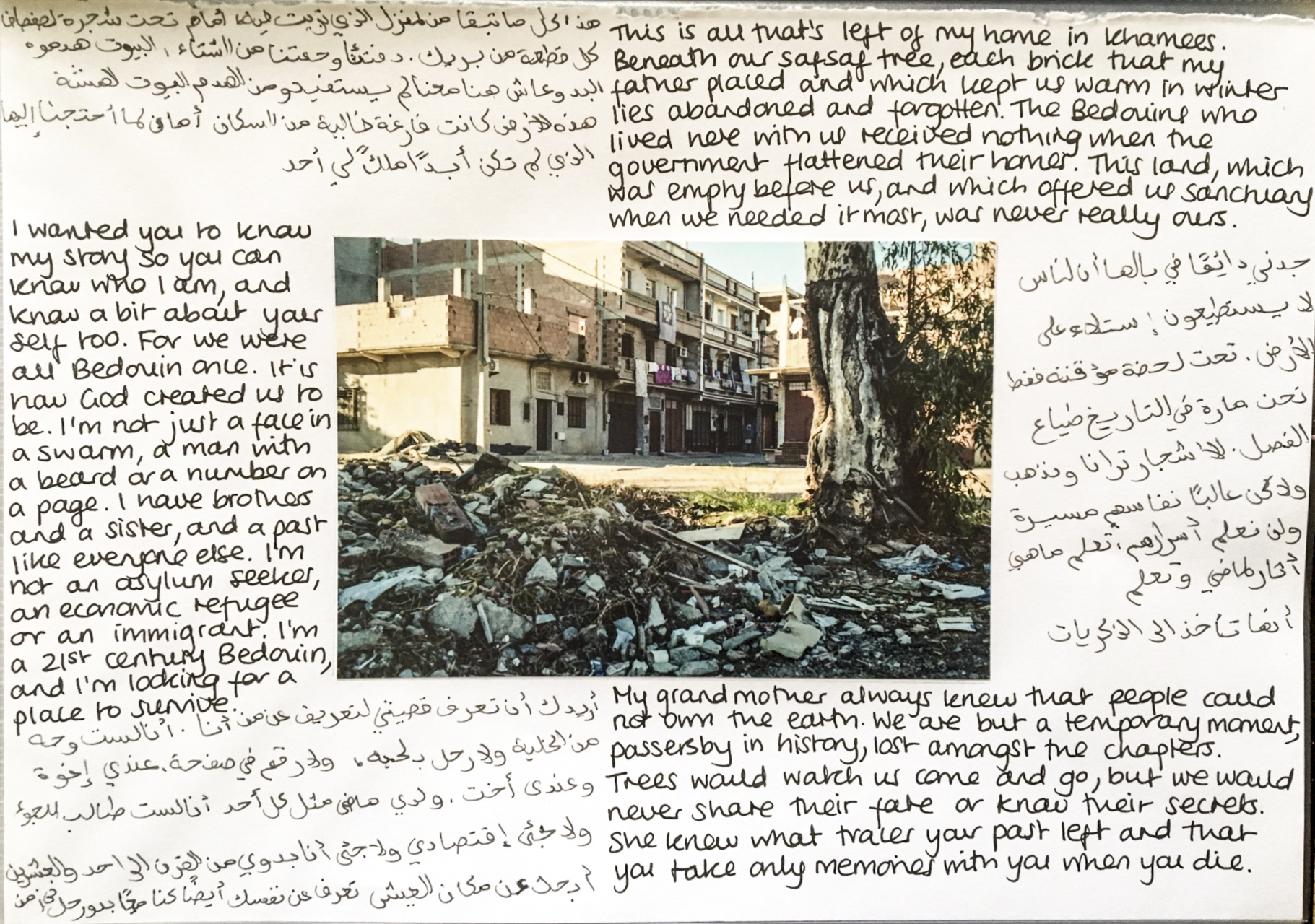

21st Century Bedouin, 2018

21st Century Bedouin is a documentary project that explores how nomadic life in Algeria has been radically transformed over the past century, through events such as French colonization, civil war and mass urban migration. The project examines this change through the lens of an individual family, whose story is told by its youngest member. Beginning in 1890s with his grandmother’s story, we find each generation experiences a common theme: migration. Migration is a polemic issue today, but we have forgotten its perpetual history, its presence everywhere in nature, and its necessity for our survival throughout human story.

The story was co-written by myself and the 21st Century Bedouin, but all the photos were taken by myself in Algeria while retracing his family’s journey over time.

Amilton Neves Cuna

Born in 1988 in Maputo Mozambique. Lives in Maputo, Mozambique

www.amiltonneves.com

Godmothers of War / Madrinhas de Guerra, 2015–2017

“Madrinhas de Guerra” or “Godmothers of War” tells the story of the Mozambican women who took part in the National Women’s Movement from 1961 to 1974. These women were sponsored by the Portuguese government to provide moral support to the soldiers fighting on the frontline during the Mozambican War of Independence. Through letter writing campaigns to soldiers – many of whom they never actually met – the Madrinhas de Guerra played a critical role in the psychological support to the colonial armed forces. Some Madrinhas went so far as to meet and regularly visit the soldiers to whom they wrote letters, developing deep relationships that sometimes lead to promises of marriage when the young men returned at the end of the war. In exchange for their support during the war, many of these women were rewarded with influential positions in society and the upper classes and some were even given houses by the Portuguese government.

In 1974, when the war of independence ended with a ceasefire agreement between the Mozambican FRELIMO forces and the Portuguese government, the National Women’s Movement officially ended. However, the Madrinhas de Guerra were ostracized within Mozambican society for their role in supporting the colonial forces. The Madrinhas de Guerra project by Amilton Neves reflects on this very important – but often forgotten – piece of history in Mozambique by visiting the homes of the Madrinhas de Guerra who still live in Maputo today. They embody the past opulence experienced during the support of the Portuguese government and the subsequent marginalization felt after independence.

Gilles Nicolet

Born in 1960 in Neuilly Sur Seine in France. Lives in Iringa, Tanzania

www.gillesnicolet.com | Instagram: @gillesnicolet

Six Degrees South 2016–2017

The Swahili Coast in Eastern Africa is a unique physical, historical and cultural entity.

For centuries now, traders have used the monsoon winds to sail their wooden dhows along its shores and coastal communities have harvested its bountiful seas for fish. Together, they contributed to the emergence of rich city ports like Lamu and Zanzibar.

But all of this is now changing. Overfishing by local and foreign ships, an increasing population, changes in weather patterns as well as the recent discovery of huge gas fields are threatening this fragile equilibrium. It could be that we are now witnessing the last of fishing and sailing traditions that had remained largely unchanged for a thousand years.

With this work I have tried to testify to the unique beauty of the Swahili Coast and to record it for generations to come.

Nura Qureshi

Born in 1977 in Bremen, Germany. Lives in Nairobi, Kenya

www.nuraqureshi.com | Instagram: @nuraqureshi

Are You Calling Me A Dog?, 2016–2017

In 1963 Kenya achieved independence after a long struggle for liberation that involved men and women mostly from the Kikuyu ethnicity or nation. Nearly sixty years later, no real liberation occurred and the heroes of that time are now slowly disappearing. A great many of the colonial settlers stayed and integrated into the society, while the men and women who fabricated the Mau-Mau liberation fight have been forgotten by newer generations and the elite. They have become too old, marginalized from society, have lost their memory or have avoided telling their descendants their traumatizing stories, or have passed away.

This past year, with the election race and the fight for land, some of these themes are being revived in Kenya, and the people who were once oppressed are using the same techniques used by their oppressors. Like a man trying to hide his scars, Kenyans have transformed the landscape; places that were once the sites of camps, executions, tortures and trials have been reimagined through the construction of schools, churches, quarries and airports.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o talks in his book “Decolonizing the mind” about the phenomenon of “shrubbing”, which refers to the mispronunciation of English words due to the interference of local Kenyan languages/dialect. The book also represented the identity of a nation in relation to the “higher language” (or civilization). It took more than 40 years for Ngũgĩ to be recognized and to gain the right to speak the native languages in the new constitution. Like a shrub that had been cut down, the Kenyan culture insisted on growing back.

The project ‘Are You Calling Me A Dog?’ reimagines the history of the Mau Mau resistance in Kenya. I used landscape and portrait photography, film and digital cameras, sometimes combined with print and ink, to recreate scenes depicting Mau Mau rituals of initiation and surrender, as well as British infrastructures of oppression.

Michele Sibiloni

Born in 1981 in Parma, Italy. Lives in Kampala, Uganda

www.michelesibiloni.com

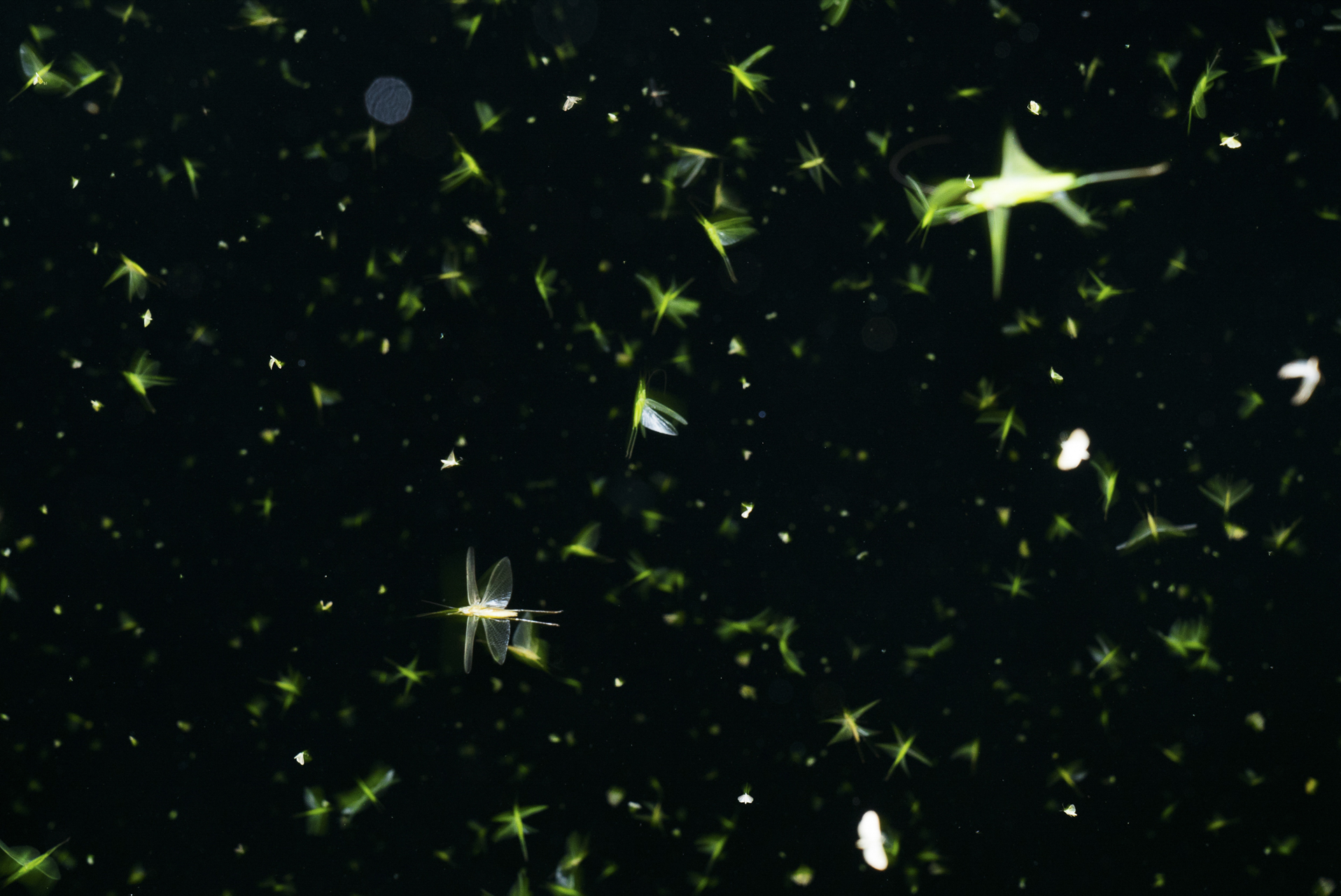

Nsenene Republic, 2014–2018

Grasshoppers, "nsenene" in the local language, are both a delicacy and a source of income in Uganda. They migrate en masse twice a year, right after the rainy seasons, flooding the sky in huge flocks before daybreak. Every night, a large part of the population stays up till twilight to hunt and sell them. Traps made of barrels and metal sheets are placed everywhere, even on rooftops, and strong light bulbs are used to attract the insects. Plastic bottles, nets and burlap sacks are also employed, and many people catch the hoppers with their bare hands. The ubiquitous presence of the crickets and the overall green shade dispersed by the night mist and the smoke of bonfires create an otherworldly scenario, enhanced by the oddness of the hunting techniques and self-made equipment. Moments of busy activity alternate with long pauses, where people try to get some rest or kill time.

Catching and eating grasshoppers is an old tradition in Uganda, and their high protein content makes them a potential food resource for the future: As stated by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization in 2013, introducing edible insects into more people’s diets could reduce world hunger and improve food safety. In recent years, though, deforestation has heavily reduced the amount of insects that migrate and climate change across Africa has made seasonal rains difficult to predict. Timing when to set the traps is crucial and doing it imprecisely can jeopardize the harvest and result in a serious loss.

Grasshoppers' hunting lies on a very precarious edge between past and future, tradition and innovation, and can shed some light about Ugandans' identity as well as about new prospects for the whole planet.

Eve Tagny

Born in 1986 in Montreal, Canada. Lives in Montreal, Canada

www.evetagny.com | Instagram: @evedeli

Lost Love, 2014–2017

Here is presented an excerpt of the photobook Lost Love. It tells the story of young love interrupted by a sudden suicide. Drawn from personal experience, yet tied to a wider context of inherited violence, the series ventures from South Africa to North America via Europe, to offer a meditation on bereavement and healing processes.

Mourners experience acute grief as a paradox. Glimpses of respite are found in the act of remembering the dead, yet whilst knowing that there is ultimately no solace. The irremediable nature of loss doesn’t allow space for consolation nor bittersweetness; one must accept a life lived with the presence of absence. Still, the need to materialize the abstract yet very real nature of absence is pressing. Thus memories, souvenirs, gestures, rituals and words become a means to do so.

Lost Love presents a journey through grief, filled with an amalgam of acts of remembrance anchored in natural spaces. As both suicide and trauma are disruptions of one’s natural cycle, the survivors’ challenge is to find ways to restore it. The book's structure follows the four seasons, as nature is here posited as the driving force onto which one can realign his perturbed rhythm and find paths of resilience.

Hence, Lot Love is not constructed solely as a eulogy for the dead, but rather as a testament for the living - a gesture towards breaking away from the legacy of trauma.